By Nolan W. Musslewhite ’25

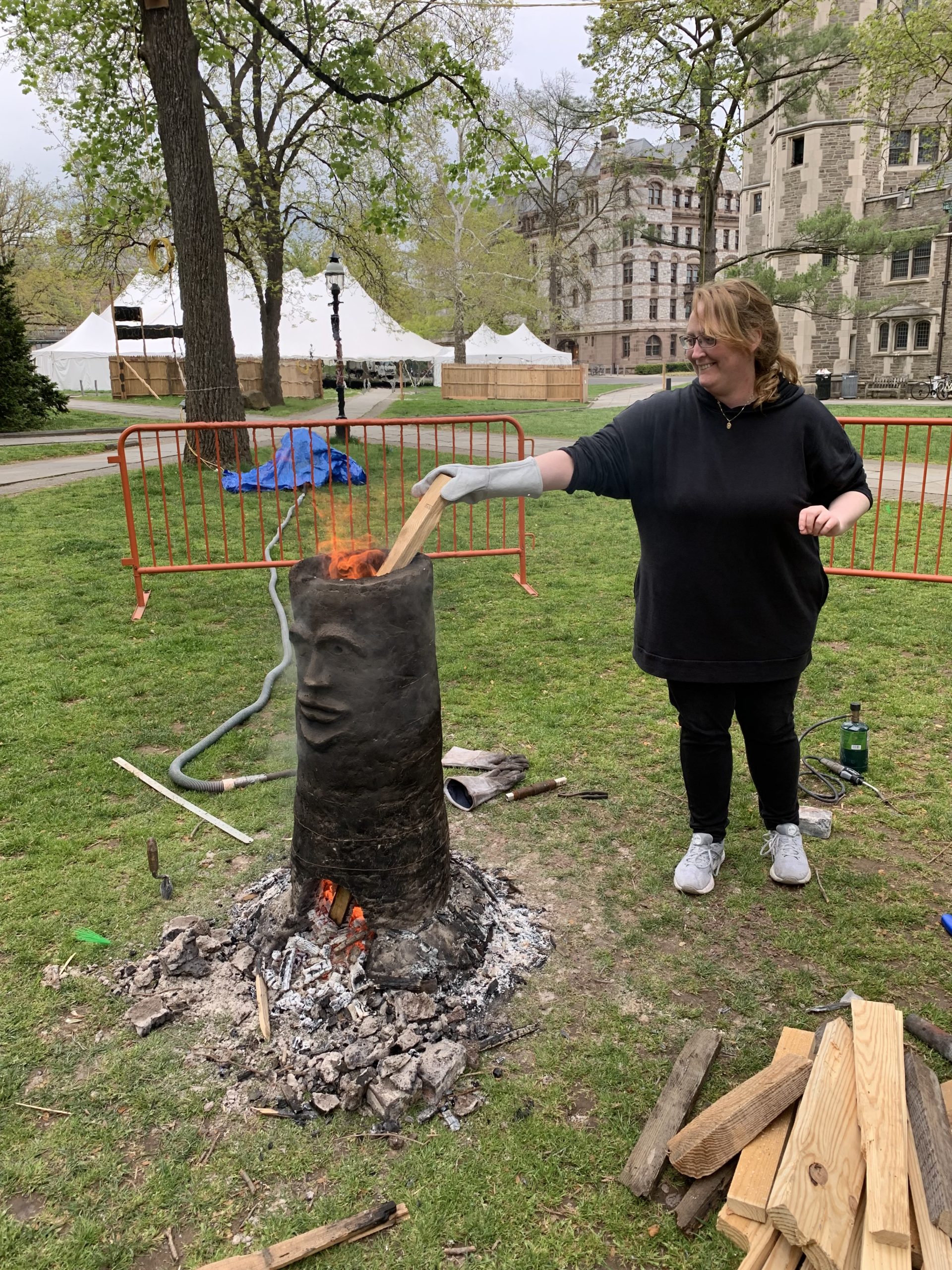

A decidedly anachronistic sight greeted any student who braved the afternoon rain for a stroll through Blair Courtyard on Friday, May 6. Towering on the grass sat a large, scowling clay tube spewing flames from every orifice. Around it buzzed a team of blacksmiths, amateur and learned alike, shoveling ore into the inferno and pulling gobs of red-hot substance from its bowels. A crowd of students and faculty looked on, mischievously grinning as sparks flew and fires roared. The pyromania was palpable.

The blacksmiths were smelting — and they were doing it the medieval way.

A daylong demonstration of medieval-style smelting, the workshop showcased an iron-producing technique that began in the Iron Age, persisted through the Classical World and the Middle Ages to Colonial America. It is also a tradition that has been intentionally preserved by smiths in West Africa, where the unique type of iron it produces holds cultural importance. Dr. Andrew Welton, a medieval archaeologist specializing in early medieval Britain, hazarded the 16-hour drive from the University of Florida, where he teaches, to lead the demonstration. The event, as part of a guest lecture for CLA247 “The Science of Roman History,” was hosted by the Environmental History Lab in Medieval Studies and co-sponsored by the Humanities Council, the Council on Science and Technology, the Department of Art & Archaeology, the Program in Archaeology, and the Department of Classics.

For Welton and for Dr. Janet Kay, associate research scholar and lecturer in Princeton’s Department of Art & Archaeology and executive director of the Environmental History Lab, the day began early. Fire dispelled the morning haze at 8 a.m. as they set a wooden scaffold aflame, baking the distinctive clay furnace from inside and out over the course of the morning. Next came the charcoal and iron ore — a mineral that includes metal and silica — the chief component of the process. Students and volunteers poured the rocky ore into the furnace throughout the afternoon. The crumbly mass cooked in the furnace for three to four hours, producing a gooey gob of lava-like material called “bloom,” a mass of iron and slag (the metallic glass-like waste product of the process).

Participants then took to the hammers, beating excess slag out of the bloom to isolate the workable component. It is this hammered product that can be shaped into tools, weapons, and other iron uses. Bloom is what distinguishes the practice of medieval smelting from modern iron smelting: Modern furnaces produce liquid iron, a larger-scale alternative to the small-use gobs of bloom that also produces higher-purity iron.

Why subject students and faculty to this arduous (albeit delightful), time-intensive procedure? “You learn much more about the process,” said Professor Caroline Cheung, assistant professor of classics and co-instructor of CLA247 with Kay. “Seeing it versus reading about it makes a big difference.” The act of smelting, much more so than the study of smelting, offers a window into earlier worlds and the people who powered them, she emphasized. Kay echoed the same thought. “We can’t get that thinking [about the medieval world] from looking at things,” Kay said. “We have to do it.”

For Welton, medieval reconstruction was a passion from youth. In high school and college, Welton participated in medieval reenactments, designing his own medieval-style garb for the events. When he began to study medieval archaeology, Welton attempted to replicate the objects he was studying by crafting a spearhead. He quickly found that modern steel produced an incomplete representation. The only solution was to use accurate medieval-era steel — a quest that led him to the furnace. Smelting also informs his current research on recycled spearheads in medieval England because existing artifacts are too rusted or warped to reveal accurate shapes and colors, so Welton crafts realistic reconstructions himself.

Perhaps the most striking component of the Princeton demonstration was the furnace itself, which held a penetrating gaze toward observers as bloom was yanked from its innards.

“The furnace is a participant in what we’re doing,” Welton said.

Giving the furnace a face and personality, he argued, recognized the integral link between the human act of producing iron and the material world that act relies upon. He compared iron in the furnace to a child in a womb, a popular motif for contemporary smelters in North America and parts of West Africa, and in historical sources from the European Middle Ages: “We have the furnace, we feed the furnace, we take care of it,” he said. “Inside it, this iron grows, and then we bring the iron out of the furnace.” Afterwards, the furnace can be used again and again without destroying it.

The ancient setup belies the activity’s complexity. Medieval smelting is a technique that remains poorly understood and that has taken decades of careful study to recreate. The workshop at Princeton showcased only a small component of the process, the smelting itself; many more steps precede and follow Welton’s showcase.

Students and spectators left the May 6 workshop with a profound sense of place. That the demanding, daylong process produced only 17.5 pounds of iron, from 65 pounds of ore and 100 pounds of charcoal, reminded observers how remarkable the towering, iron structures of the modern cityscape are. Smelting the ancient way also brought into sharp relief the oft-overlooked actors of history: blacksmiths who toiled in the early forges of the Iron Age, laborers who sweated in the hot smithies of ancient Rome, settlers and their enslaved African captives who hammered tools from the ancient ores of the Appalachian Mountains. To smelt as the ancients did links one to the grand arc of human history and contextualizes our moment in it.